Alaunt Veauntre Origins

The “Alaunt isn’t a breed, it’s a prototype that represents a pre-industrial landrace working dog, not a standardized breed. Long before kennel clubs, closed studbooks, or cosmetic selection, dogs were shaped by function, geography, and human need. Historically the “Alaunt” was an umbrella term applied to large, athletic catch-and-combat dogs used across Eurasia for war, livestock control, hunting dangerous game, and estate protection. They weren’t uniform in appearance, but they were consistent in purpose. What unified them wasn’t a look - it was capability.

A Prototypical Mastiff Type Precursor

Rather than representing a direct ancestor of any single modern breed, the Alaunt is more accurately described as a prototypical or foundational working type from which multiple modern hounds, mastiffs and catch-dog lineages later diverged. Prior to industrialization and the formalization of breed standards, canine populations remained relatively open. Selection pressures emphasized performance and survivability, resulting in dogs that were structurally efficient and behaviorally suited to work rather than a uniform appearance.

As human societies became more specialized, these broad landrace populations were gradually subdivided and refined through wars, migration, colonization and trade. This gave rise to heavier guardian type mastiffs, specialized hunting dogs and the beginning of specific breed development. In this context, the Alaunt represents a functional precursor, not a standardized blueprint.

In medieval Europe, the Alaunt type was functionally classified rather than stylistically standardized. In sources such as the French Livre de chasse (1387-1389) by Gaston III, Count of Foix (a foundational text on hunting and working dogs of the period), related classifications distinguished the dogs by purpose.

Traditional Alaunt classifications included:

Alaunt Gentil - lighter, sighthound-influenced dogs for coursing

Alaunt Veauntre (also spelled Vautre in historical sources) - the running mastiff optimized for sutained pursuit and engagement

Alaunt de Boucherie - heavier, grip oriented catchdogs used in work with livestock and boar.

These distinctions reflect function over form: dogs varied in build depending on task but shared key performance traits.

The accompanying illustration is reproduced from Dogs, Volume X of Jardine’s Naturalists’ Library (1840), authored by Charles Hamilton Smith. This work belongs to an early period of canine scholarship that predates the formal establishment of kennel clubs, closed studbooks, and standardized breed definitions. As such, it documents dogs as functional types rather than as fixed breeds.

Charles Hamilton Smith describes the subject as a “brindle catch dog, used in France 100 years ago; strong headed but tight mouthed” noting its historical use in the pursuit of large and dangerous game, including wolves. The terminology employed reflects contemporary functional classifications, wherein dogs were identified by role and utility rather than by uniform appearance.

The morphology depicted - moderate cranial breadth, a functional (non exaggerated) muzzle, erect ears (cropped), and overall athletic construction - aligns with descriptions of pre-industrial catch and combat dogs commonly associated with hunting Alaunt-type populations. While the illustration should not be interpreted as a definitive representation of a singular “Alaunt breed”, it provides valuable insight into the range of phenotypes present within broader landrace working dog populations from which later mastiff and bulldog types emerged.

The Alaunt Gentil

The Alaunt Gentil represents the most refined and least force-oriented expression of the historical Alaunt continuum. Medieval sources describe the Gentil not as a diminished Alaunt, but as a specialized variant shaped by pace, endurance, and responsiveness rather than gripping power. Where the Véauntre was expected to pursue and engage, and the de Boucherie to seize and hold, the Gentil was valued for its fluid movement, handler sensitivity, and sustained participation in the hunt.

In Le Livre de Chasse (1387), Gaston III of Foix distinguishes dogs not by aesthetic uniformity but by their role within coordinated hunting strategies. The Alaunt Gentil occupied a position closer to the mounted hunter—capable of traveling long distances, responding readily to direction, and maintaining composure within structured hunts. This classification suggests a dog lighter in frame, more elastic in movement, and less committed to prolonged gripping than its heavier Alaunt counterparts.

15th Century by Antonio di Puccio Pisano - Alaunt Gentile Type

Functionally, the Gentil likely incorporated greater sighthound influence, emphasizing:

Efficient, ground-covering movement

Reduced mass relative to height

Heightened responsiveness to human direction

Endurance over raw physical domination

Despite its refinement, the Gentil remained unmistakably Alaunt in character. It was not fragile, ornamental, or purely coursing-oriented. Rather, it occupied the upper boundary of athletic lightness within the Alaunt spectrum, retaining sufficient substance and nerve to operate alongside heavier dogs in dangerous game pursuits.

Historically, the Gentil’s role underscores an essential truth of the Alaunt type: variation existed by necessity, not preference. The Alaunt was not a single form but a functional family, adapting its outline to task while maintaining core working traits—mental stability, physical durability, and cooperation with humans.

In the modern context, the Alaunt Gentil provides valuable insight into the structural limits of refinement within working mastiff-derived dogs. It serves as a reference point rather than a breeding target for SavantK9, reminding us that speed and elegance must never exceed utility, and that reduction of substance without purpose ultimately compromises function.

The Gentil stands as a historical counterbalance to exaggeration—demonstrating that even the lightest Alaunts were still working dogs, shaped by necessity and restrained by performance.

The Alaunt Veauntre

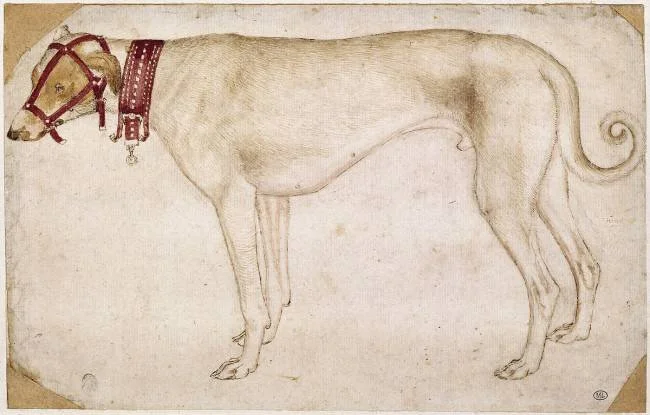

Chien muselé et portant un collier, debout, de profil vers la gauche - 15th Century by Antonio di Puccio Pisano

The term Veauntre (from Old French, meaning “to hunt” or “to pursue”) describes a dog built not just to fight, but to move. As medieval hunting practices evolved, the Alaunt Veauntre became the prototype for what later historians and breeders call the “Running Mastiff.” This term describes mastiff-type dogs that retained athletic speed, functional agility, and working endurance. These were the dogs who were deployed against boar, bear, wolves and deer - often amongst a team of sighthounds who initatied the chase, it was the Alaunt Veauntre that is thought to have finished the work.

Unlike heavier mastiff types, the Veauntre was characterized by:

A lean, long-legged frame capable of sustained galloping

A deep chest and flexible spine for endurance and recovery

A powerful mastiff head and jaw for grip-and-hold work

A clear, forward temperament—bold, independent, and pressure-proof

15th Century by Antonio di Puccio Pisano

Genetic and Functional Legacy

The Alaunt Veauntre is widely considered foundational to several breeds or breed types, including:

English Mastiff (early athletic forms)

Bullmastiff (via butcher’s dogs and estate catch dogs)

Great Dane (especially through German boar-hunting lines)

Dogo Argentino (via Spanish Alaunt influence in the Americas)

Presa Canario and other Iberian catch dogs

In Britain, Norman influence following 1066 likely introduced Alaunt-type dogs that blended with native mastiffs, producing faster, more athletic “running” mastiffs used for deer coursing and bull baiting.

Decline of the Alaunt Veauntre

The Alaunt Veauntre did not disappear suddenly but faded as:

Firearms reduced the need for large catch dogs

Forest laws restricted noble hunting

Dog breeding shifted toward specialization and aesthetics

By the 17th–18th centuries, the Alaunt was no longer recognized as a distinct type, but its genetic and functional blueprint survived in multiple working breeds.

The Iberian Influence: Mastins, Alanos, and Lebrels

When the Spanish and Portuguese conquistadores crossed the Atlantic, they did not arrive alone. Alongside steel, horses, and doctrine came dogs—dogs bred for war, pursuit, and survival at the edges of empire. These animals were not ornamental companions but functional instruments of conquest, selected under extreme conditions. Among them were the Mastín, the Alano, and the Lebrel—three types whose convergence profoundly influenced what we now recognize as the Alaunt type. The New World, brutal and vast, acted as a crucible in which Iberian dogs were tested, blended, and refined. The conquistadores, knowingly or not, became agents of canine evolution.

The Mastín: Mass, Authority, and Holding Power

The Mastín Español represented the oldest and heaviest end of the Alaunt spectrum. Descended from ancient livestock guardians, mastíns brought size, bone, and psychological dominance. These dogs were used to guard camps, intimidate populations, and protect supply lines. Their presence alone conveyed authority.

In the context of conquest, mastíns contributed:

Substance and skeletal strength

Thick skin and loose connective tissue, offering protection in combat

Calm nerve under pressure, allowing them to hold ground rather than scatter

While not pursuit dogs, mastíns anchored the Alaunt type with mass and power. In crossings with lighter dogs, they added durability and the ability to engage and hold human or animal adversaries once contact was made.

The Alano: The Core War Dog

If the mastín was the anchor, the Alano Español was the engine. The Alano was a true dog of war and cattle—gripping, driving, and controlling large, dangerous targets. Bred for the agarre (the hold), Alanos were used against indigenous fighters, escaped captives, and feral livestock alike.

Key contributions of the Alano to the Alaunt type included:

Forward aggression tempered by handler control

Strong jaw mechanics and full-mouth gripping style

Medium-heavy frame capable of speed, impact, and endurance

High pain tolerance and persistence

Historical accounts repeatedly describe these dogs being armored, fed rations equal to soldiers, and deployed tactically. In the New World, selection favored Alanos that could travel long distances, tolerate heat, and function with minimal support—pressures that pushed the type toward a more athletic, enduring form.

The Lebrel: Speed, Sight, and the Running Mastiff

Often overlooked in discussions of conquest dogs, the Lebrel (Iberian sighthound) was nonetheless critical. Spanish lebreles brought speed, visual acuity, and pursuit instinct. They were used to run down fleeing people, hunt game to feed expeditions, and scout terrain ahead of columns.

When crossed with Alanos and mastín-influenced dogs, lebreles contributed:

Length of leg and elasticity of stride

Aerobic efficiency and heat dissipation

Sharper visual hunting drive

A lighter, more mobile outline

This infusion produced what later historians and breeders would recognize as a running Alaunt—a dog capable of both pursuit and engagement. Not merely a catch dog or guardian, but a multi-purpose war and hunting animal adapted to vast distances and unpredictable conditions.

The Spanish imperial period tested these dogs in extreme environments: long distances, heat, sparse, and diverse roles (guarding, hunting, pursuit and combat). Under such pressures, dogs that could move well, endure, and engaged survived and reproduced - echoing the same performance balance recorded in France centuries earlier.

Legacy of the Conquistador Dogs

Though the age of conquest ended, the dogs endured. Their genetic and functional legacy echoes in many modern working mastiff-derived dogs, particularly those emphasizing movement, endurance, and utility over exaggeration.

The Alaunt type—shaped by mastín mass, Alano courage, and lebrel speed—stands as a reminder that breeds are not born in show rings, but in history. The conquistadores did not set out to create a new dog, yet through war, survival, and adaptation, they helped forge one of the most formidable functional types the world has known.

In understanding this lineage, we do not celebrate conquest—but we acknowledge how human conflict, movement, and necessity sculpted the dogs that walked beside us through it.

References

Díaz del Castillo, B. (1568). Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes.

https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/historia-verdadera-de-la-conquista-de-la-nueva-espana/

Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, G. (1535). Historia general y natural de las Indias. Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes.

https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/historia-general-y-natural-de-las-indias/

Gómara, F. L. de. (1552). Historia de la conquista de México. Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes.

https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/historia-de-la-conquista-de-mexico/

Hancock, D. (2012). Dogs of the shepherds: A review of the pastoral breeds. The Crowood Press.

https://www.crowood.com/products/dogs-of-the-shepherds

Hancock, D. (2015). The mastiff in Britain. The Crowood Press.

https://www.crowood.com/products/the-mastiff-in-britain

Phébus, G. (1387). Le livre de chasse. Bibliothèque nationale de France (Gallica).

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10507238z

SavantK9 Working Library. (2025). The Alaunt Véauntre.

https://www.savantk9.com/library/2025/12/15/the-alaunt-veauntre

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Alaunt. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alaunt

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Alano Español. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alano_Espa%C3%B1ol

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Mastín Español. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mast%C3%ADn_Espa%C3%B1ol

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Galgo Español. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galgo_Espa%C3%B1ol

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Livre de chasse. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Livre_de_chasse